There's been a lot of talk in education about gamification. The idea is to use game mechanics, dynamics, and frameworks to promote desired behaviors. This concept is broadly used in marketing when companies use games to increase consumerism in the form of participation or purchasing. Think the McDonald's Monopoly game or when your gym offers incentives if you spend more time there.

In education the goals are only slightly different. Teachers certainly use gamification to increase consumption and engagement, but we are also interesting in helping students "learn better" and "care more" about school, goals that lead to increases in consumption and engagement. As a result, gamification in education might be more about process and emotion than the same practices in business.

But enough theory. I'm certainly no expert. You can read some of the research I consulted when I started this piece here.

So yesterday I decided to "gamify" my College Algebra class. We were on a 80 minute block schedule day and the planned lesson was a set of word problems, a task that my students dislike on a good day. The class meets at 8am and my seniors drag in most days clutching a cup of coffee like a life preserver. When I told them we were working on word problems, there was moaning. When I mentioned that they would have to move around, there was more moaning. "Can't we just work in groups?" I ignored them.

The task was simple. They were assigned ten problems and divided into pairs with a single calculator. Every five minutes they moved on to the next problem with a new partner. At the end of the cycle we graded the papers and the student that scored the highest won a prize. Students needed to correct their errors as homework.

By the end of class they were no longer sleepy. I am confident that I had every student on task for the entire period. Every student score a 90% or above. Students could ask for help if needed, but frankly, they asked only one question the entire time. They just figured each problem out, the strong students helping the weaker as needed. There was plenty of laughter and movement, two factors that contribute to a lot of successful games and learning.

I have colleagues all over my school trying out gamification. Some have created elaborate games where students earn individual badges and team points using a Harry Potter model. Others are like me, use simple games to enhance learning of topics that are particularly challenging or to foster an interest in reviewing before a test.

The only question that still needs asking is whether gamification helped students meet any of the goals. Did gaming yesterday's class help my students learn better and/or care more about school and as a result increase consumption of and/or engagement in math. I'm going to ask them today in class, but what do you think?

Does gamification work in your classroom? Can you tell me about ways you have used games to meet your educational goals?

Friday, March 28, 2014

Thursday, March 27, 2014

a thousand little pieces

This week we had a normal Wednesday in the life of my school. When I say normal, I mean that nothing unusual happened. For example, in addition to teaching, I had 3 important meetings. One was about the progress my department is making in using technology, the second was about developing a scope and sequence document for the math department, and the third was an informational pitch on a new learning management system the school is considering. All of these things are important to my job, but not particularly unusual.

What got me thinking was not my three little meetings, but the fact that they are such a small part of the workings of our school. Tons of events went on, things that make this school move forward, and for every item I can list here, there were likely dozens of others happening that I know nothing about. For example, 150+ different sections of courses were taught today, a day in which students had only three 80 minute classes. We had separate chapel services for both the middle and upper school students. Upper school students enjoyed listening to a career day speaker talk about working for Disney. Our visiting writer held a creative writing workshop for interested students and will do a reading of his own work this evening. Our thespian troupe left for state competition this afternoon and our baseball and softball teams had games today. The rest of our spring sports teams (tennis, lacrosse, track) had practice and there was a faculty yoga class. Prospective students and their families toured our campus, there was a meeting about the construction of a new middle school, the drum line had practice, and students made up tests after school. I sincerely hope all 1000 people on this campus stopped for a moment or two for lunch. After school bathrooms will be cleaned, floors swept, trash cans emptied. The phones were answered, the grass mowed, and the mail delivered. Someone paid the bill to keep the lights on.

It seems so easy when you peer at a school through the tiny peephole afforded the outside world, but schools are a thousand moving parts, dozens of interlocking pieces that build not just a pile of homework for kids, but a life for every member of the community. Every adult in my community is an educator, whether they are in the classroom or not and every single teacher also coaches a sport or sponsors a club, supervises the cafeteria or administers tests after school.

People often wonder what teachers do all day and why days that end at 3:00 are so much longer. I challenge you to ask a teacher what she does all day, to ask your student what goes on at his school beyond the classes. I bet you'll be surprised, even awed as I am by how much is expected of the people that work so hard to educate our kids.

Maybe that's not what schools should be, but who am I to say? It's hard to find time to look up for a moment and see the whole puzzle when you're wrapped up in a thousand little pieces.

What got me thinking was not my three little meetings, but the fact that they are such a small part of the workings of our school. Tons of events went on, things that make this school move forward, and for every item I can list here, there were likely dozens of others happening that I know nothing about. For example, 150+ different sections of courses were taught today, a day in which students had only three 80 minute classes. We had separate chapel services for both the middle and upper school students. Upper school students enjoyed listening to a career day speaker talk about working for Disney. Our visiting writer held a creative writing workshop for interested students and will do a reading of his own work this evening. Our thespian troupe left for state competition this afternoon and our baseball and softball teams had games today. The rest of our spring sports teams (tennis, lacrosse, track) had practice and there was a faculty yoga class. Prospective students and their families toured our campus, there was a meeting about the construction of a new middle school, the drum line had practice, and students made up tests after school. I sincerely hope all 1000 people on this campus stopped for a moment or two for lunch. After school bathrooms will be cleaned, floors swept, trash cans emptied. The phones were answered, the grass mowed, and the mail delivered. Someone paid the bill to keep the lights on.

It seems so easy when you peer at a school through the tiny peephole afforded the outside world, but schools are a thousand moving parts, dozens of interlocking pieces that build not just a pile of homework for kids, but a life for every member of the community. Every adult in my community is an educator, whether they are in the classroom or not and every single teacher also coaches a sport or sponsors a club, supervises the cafeteria or administers tests after school.

People often wonder what teachers do all day and why days that end at 3:00 are so much longer. I challenge you to ask a teacher what she does all day, to ask your student what goes on at his school beyond the classes. I bet you'll be surprised, even awed as I am by how much is expected of the people that work so hard to educate our kids.

Maybe that's not what schools should be, but who am I to say? It's hard to find time to look up for a moment and see the whole puzzle when you're wrapped up in a thousand little pieces.

Tuesday, March 25, 2014

dazed and confused

|

| Photo Credit |

That was August.

No such luck on the day after spring break. Mostly I got that stunned look of a deer in headlights, with no real thoughts other than,

"Why does school start so early?"

I was kind of thinking that myself when the alarm went off. Then I got up, made some coffee, and got started on another great day at the job I love.

Monday, March 24, 2014

and we're back...

|

| Image credit |

The only way to get to summer vacation is to make it through the 4th quarter... here we go... 29 class days remain with my seniors, 33 with my underclassmen, 25 with my AP students...

Tuesday, March 18, 2014

cost benefit analysis

I teach several different math subjects, AP Calculus and Statistics being two of them. In both classes students have to do their homework online. For each problem they get 3 tries to type in the correct solution. Most of my calculus students want to get a perfect score and will work literal hours to get the last 2 points. Some of my statistics students can barely be bothered to do the assignments at all.

My questions are many.

- Why do some students become perfectionists, literally go overboard in their striving for A's in school while other don't seem to care at all?

- How do we create a balance between over the top and no effort at all?

- Is is really possible for teenagers to do cost-benefit analysis?

Monday, March 17, 2014

would you like some cheese with that?

10 things math students whined about in class yesterday while playing bingo...

- the direction of the scrolling feature of the track pad on a computer

- the fact that they don't know what's going on after they don't read their emails

- the rigorous security on their online homework site

- the time remaining before lunch

- the fact that their calculator cannot read their minds

- converting decimals to fractions

- their lack of a writing utensil

- the unit circle in trigonometry

- problems that take a long time to solve

- simplifying their answers

- the number e

OK, that was 11 things, but who's counting?

a perfect day

Once a week I have block period with my students, 80 minutes with them to think, to talk, to play. Each week I try to ask them something about themselves, a question of the day. It helps me know and understand them better, to make that connection of shared experiences that allows me to try to motivate and inspire them to do better. This week I asked them to help me build a perfect day. Each person was able to contribute one thing to our perfect day. It could be an activity, a thing, an idea, whatever they wished. We recorded it on the board, a picture of some sixteen year olds' perfect day...

Thursday, March 13, 2014

3.14 reasons for leadership

I am the sponsor of our school's Mu Alpha Theta chapter and each year we elect officers to do the work of spreading the word that math is cool! I am proud of our chapter. The members spend hundreds of hours tutoring their classmates and participating in monthly competitions. The capstone event is our yearly celebration of PI Day, a schoolwide event where pie is provided and all our students learn a little about PI.

I am the sponsor of our school's Mu Alpha Theta chapter and each year we elect officers to do the work of spreading the word that math is cool! I am proud of our chapter. The members spend hundreds of hours tutoring their classmates and participating in monthly competitions. The capstone event is our yearly celebration of PI Day, a schoolwide event where pie is provided and all our students learn a little about PI. This year the officer in charge of the event got sick and the remaining officers got an important lesson in leadership. As we all stood around at 7:15am staring at 66 pies, it was clear that the person who knew how many pies needed to be delivered to each classroom was in fact home in bed.

It was a mad scramble, but eventually the pies were delivered and the students sprinted off to their first period class. What I love about this event is not that it was chaotic, but that it was a great opportunity for the rest of the officers to see what happens when leadership is not present. They had to step up and make a new plan to get the work done. It wasn't pretty, but it worked, and I know these students learned an important lesson, not about math, but about life.

I want to remind all of my adult friends, teachers and parents, that giving kids a chance to lead, fall down, and pick themselves up is a vital part of the school experience. Of course we adults can do things better, but that's only because we're more experienced. Someone gave us a chance to plan something. Maybe it didn't go perfectly, but we learned.

PI Day is actually Friday, March 14, but we do not have school. Thus I wish you happy PI Day and hope you enjoy a piece of pie.

We begin Spring Break on Friday as well so I will be off line for the next week. I hope to finish grading and write some comments, plan the rest of this school year, get some rest, and eat a slice of pie... maybe two.

Photo Credit

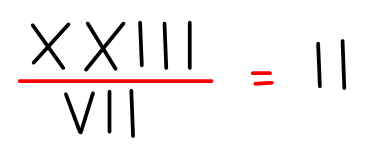

13 matchsticks are arranged to form the Roman numeral equation 23/7 = 2. This is obviously wrong. Move one of the matchsticks to make the equation "correct." (No fair moving the division bar or the equal sign. )

Wednesday, March 12, 2014

why you should care about Rick Roach

|

| Photo Credit |

I won’t seek a 5th term on the Orange County School BoardMy many years as an Orange County’ School Board member representing District 3 have been rewarding beyond description. What I’ve learned, my friendships with students, teachers, administrators, constituents, members of civic and business organizations and fellow board members, the satisfactions of problems solved—even wrestling with problems that have no good solution—have unquestionably changed me for the better.But I’m leaving in November, and I want to say why. I’m not leaving because I feel I can no longer make a difference in Orange County, but because I want to make a bigger difference than my role allows.First, after 42 years as an educator and 16 as a school board member, I no longer recognize my profession. People who have never taught, or have been out of the classroom too long to remember teaching’s complexity, now control the institution. Education policy makers, who wouldn’t dream of telling surgeons how to wield a scalpel or telling pilots how to land an airliner, seem perfectly comfortable dictating rigid guidelines for teachers.Second, the push to standardize has gotten out of control. As the world’s problems grow increasingly complex, we don’t need standardized minds but fresh thinking. We’ve long led the world in creativity and ingenuity, but those now running the education show in Washington and Tallahassee have steadily taken away the trust, freedom and respect that once allowed teachers to use their strengths effectively. I want to use my knowledge and experience to help solve these problems.Finally, it’s the drive to test, test, and re-test that leads me to conclude that it’s time for me to do more to change this agenda. That a score on a single, machine-scored, multiple-choice test can erase 180 days of work and override teacher judgment is insulting. Test manufacturers say, in print, that no single measure is accurate enough to base life-changing decisions on it, but their warnings are ignored, as is the fact that failure rates are set even before the tests are administered.We’re so caught up in the testing frenzy, we even insist on testing kids with severe brain impairments, or who have little or no brain at all. Immigrant children who arrive in America speaking no English are tested after only one year, when research clearly says it takes at least four or five years to become proficient in a new language. Pass-fail cut scores ignore margins-of-error, forcing kids to repeat a class for a full year because they missed the cut by a point or two. This has to end.It has been my pleasure to serve you for the past 16 years and I want to continue to be your voice and search for common sense solutions, always putting our students first. My passion for real education tells me to get closer to the battlefield where decisions are being made. There are better ways to educate than we’re using and I want to find and promote them.Yours in Education,Judge “Rick”Roach

Monday, March 10, 2014

second opinion, please

I'm trying to decide if I'm a Madame Benevolent Dictator looking out for my students' health and well-being or a permanent Princess Crankypants. As you know, I can be cranky at times, but I'd like to think I'm basically good. Here's your chance to give me a grade.

I'm trying to decide if I'm a Madame Benevolent Dictator looking out for my students' health and well-being or a permanent Princess Crankypants. As you know, I can be cranky at times, but I'd like to think I'm basically good. Here's your chance to give me a grade. There's this group of 9th graders that plant themselves in the hallway of my building during lunch. They talk about teenager stuff and they're not bad kids, but they are loud. Monday I threw them out the door on the grounds that it was a beautiful day and they were loud enough for me to hear them 3 doors down. I have no doubt I know what they think of me, but I'd like a second opinion.

Benevolent Dictator or Princess Crankypants... What do you think?

of fishes and wishes...

When I was a kid, my mom used to say, "If wishes were fishes, we would all live in the sea," every time I expressed my longing for a ridiculous toy, dessert, or opportunity. I think this is a pretty common practice, as it is important for children to hear the word "no" sometimes.

When I was a kid, my mom used to say, "If wishes were fishes, we would all live in the sea," every time I expressed my longing for a ridiculous toy, dessert, or opportunity. I think this is a pretty common practice, as it is important for children to hear the word "no" sometimes. A few years a ago representative from the Orlando Magic came to our school and offered students a pair of free tickets to a game if they would share their dreams for the future. Some of our students could not even tell us their dreams. As a result, in my leadership class I assign students the task of looking to the future and vocalizing their dreams. I think this is an important activity. By vocalizing our dreams, we can begin the conversation of why and how that can actually lead to dream fulfillment and success.

Dreams don't just happen, they are built through hard work and sacrifice, hearing the word "no" and trying again, believing in the dream's value and the inherent value in the self. Dreams are incredibly important and so I am asking you to share your ideas, to build a dream with me...

If you had one wish for education, one dream for your child, for your school, for teachers, for education, what would it be?

Will you share your dream in the comments? If you could have one wish, one swim in the sea, what would it be?

P.S. My childhood dream was to be secretary of education.

My current wish is to get politicians out of education.

Your turn!

Wednesday, March 5, 2014

can 5-year-olds learn calculus?

|

| You can check out this book by Maria Droujkova here |

Some summary points:

- The way we teach math is contrary to the way the human brain, children, or mathematics works.

- Early emphasis on arithmetic is bad for kids and can lead to negative attitudes about math.

- The complexity of an idea and the difficulty of doing it are different. An idea can be simple to understand but difficult to do.

- Games and free play are efficient means by which children learn.

- By exposing children to the ideas of calculus and algebra early you build a "canopy of high abstraction that does not whither."

- There are levels of understanding and there is no expectation that children will have a formal understanding of the mathematics early on.

- Children need a voice in their learning and the ability to choose what and how they learn.

- Push back to these ideas comes from two camps. The first are those that think parents will push their kids too hard when they find out that they can "do calculus" in elementary school. The second group thinks that essential computational skills will be lost.

I have been teaching AP Calculus AB for more than 20 years and there is very little about this curriculum that I have not mastered at this point. I have a clear understanding of the large questions that are answerable through the use of calculus and the details required to reason to a correct solution to such questions.

I think that I have some real questions about the practice of leading children to calculus suggested by Maria Droujkova. Some of it comes from the fact that for the past twenty years, my most successful calculus students were those that had completely mastered the foundational arithmetic skills required in support of the calculus. I can certainly have a conversation about fractals and even wander into the ideas of infinitesimals with a 1st grader, but there is literally no chance that anything will come of that conversation other than, "This is cool." Even if this child was taught some kind of procedural steps that led to a solution to a question they asked, I am sure they would not have any understanding of why the did any of the steps or what any of it meant.

One of the hardest things I have to do is teach my students how to see the forest for the trees. Every day we look at the toolbox that is calculus and discover the amazing problem solving tools that allow us to solve both practical problems of changing quantities and growing volumes, but also to logically prove why a particular formula from geometry or technique from algebra actually works. In many ways I feel like calculus is a culmination of a dozen years of mathematics, giving students the means to literally fly above the trees of questions and see the connections, the intertwining branches of the entire forest.

So perhaps this really comes down to a matter of semantics. What does it mean to teach a 5-year-old calculus? What does it mean to teach the same subject to a high school student? It's simply not the same thing. And in my mind, that's ok. Showing a 5-year-old that math is cool is absolutely fine with me. Please, go ahead and spark curiosity! Show kids fractals, wow them with infinity, expose them to the reasons why we want and need mathematical knowledge.

But while they're building towers with Legos and creating origami snowflakes, don't forget to teach them to make change, calculate a tip, and choose a cell phone plan. We need those skills too, maybe even more.

Tuesday, March 4, 2014

see now I'm just mad

Yesterday I had a massive computer meltdown and I know it's supposed to be TEDTuesday, but I have been thinking about this post all weekend and I've decided I really need to say something, but before I do, let me tell you a story.

Consider Mary. Mary enrolled in Weight Watchers. Every week she went to a meeting and weighed in. One week she went in and did really well. She lost 5 pounds! Everyone gave her high fives. She even won the weekly award for the group! Woo hoo! The next week she weighed in, but she only lost 2 pounds. Now 2 pounds is still awesome, but it was not as good as the previous week so the group ridiculed her. It turns out that they expected her to lose more and more weight every week. It didn't take Mary long to quit the group.

Am I crazy or does this seem silly? It doesn't make sense to ask people to continally lose more and more weight. It also makes no sense to ridicule her efforts,. Most people respond pretty poorly to ridicule. If Mary were on The Biggest Loser, I might think about this scenario differently, but this is not a game show and no Weight Watchers program would ever do such a thing.

Now consider Simone Ryals. In 2012 she was a state finalist for a Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching Program. Her students did exceptionally well in science, many earning top scores, 5's on the State Science exam, an exam that has a 40% passing rate.

But this year the state raised the standards on the test so that students must score even higher to earn a 5. This I understand. States are in the business of slowly raising standards, of pushing kids further and further in the hopes that we can get American education back on track. Simone's students still did well, but they did not score as highly on the State Science exam. Her students earned more 4s and 5s that were not quite as high.

What yanks my chain is that Simone's students' lower scores mean that she is now ranked as an inferior teacher. Despite the fact that her students still more than passed the exam that 60% failed, she is inferior. And worse, her name will be published in the local papers so that parents will know which teachers are "great" and those that are "inferior."

Look, I get it. We are all trying to improve education. Parents want information and test scores may seem like a good way to measure a teacher's effectivness. But it's not that simple and anyone with a lick of sense knows that we need teachers like Simone Ryals. We can continue to measure a teacher's effectiveness by a single test score, to force teachers to work in a rigged system, or we can do better and create a system that is fair and helps all teachers and students improve. Our kids deserve it. Simone Ryals deserves it. Anyone who disagrees should feel free to become a 5th grade science teacher. If we don't change the system, we're going to need them.

Photo Credit

Consider Mary. Mary enrolled in Weight Watchers. Every week she went to a meeting and weighed in. One week she went in and did really well. She lost 5 pounds! Everyone gave her high fives. She even won the weekly award for the group! Woo hoo! The next week she weighed in, but she only lost 2 pounds. Now 2 pounds is still awesome, but it was not as good as the previous week so the group ridiculed her. It turns out that they expected her to lose more and more weight every week. It didn't take Mary long to quit the group.

Am I crazy or does this seem silly? It doesn't make sense to ask people to continally lose more and more weight. It also makes no sense to ridicule her efforts,. Most people respond pretty poorly to ridicule. If Mary were on The Biggest Loser, I might think about this scenario differently, but this is not a game show and no Weight Watchers program would ever do such a thing.

Now consider Simone Ryals. In 2012 she was a state finalist for a Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching Program. Her students did exceptionally well in science, many earning top scores, 5's on the State Science exam, an exam that has a 40% passing rate.

But this year the state raised the standards on the test so that students must score even higher to earn a 5. This I understand. States are in the business of slowly raising standards, of pushing kids further and further in the hopes that we can get American education back on track. Simone's students still did well, but they did not score as highly on the State Science exam. Her students earned more 4s and 5s that were not quite as high.

What yanks my chain is that Simone's students' lower scores mean that she is now ranked as an inferior teacher. Despite the fact that her students still more than passed the exam that 60% failed, she is inferior. And worse, her name will be published in the local papers so that parents will know which teachers are "great" and those that are "inferior."

Look, I get it. We are all trying to improve education. Parents want information and test scores may seem like a good way to measure a teacher's effectivness. But it's not that simple and anyone with a lick of sense knows that we need teachers like Simone Ryals. We can continue to measure a teacher's effectiveness by a single test score, to force teachers to work in a rigged system, or we can do better and create a system that is fair and helps all teachers and students improve. Our kids deserve it. Simone Ryals deserves it. Anyone who disagrees should feel free to become a 5th grade science teacher. If we don't change the system, we're going to need them.

Photo Credit

Monday, March 3, 2014

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)